Man Knows Not His Time.

“So teach us to number our days, that we may apply our hearts unto wisdom.”—(Psalm 90:12, KJV)

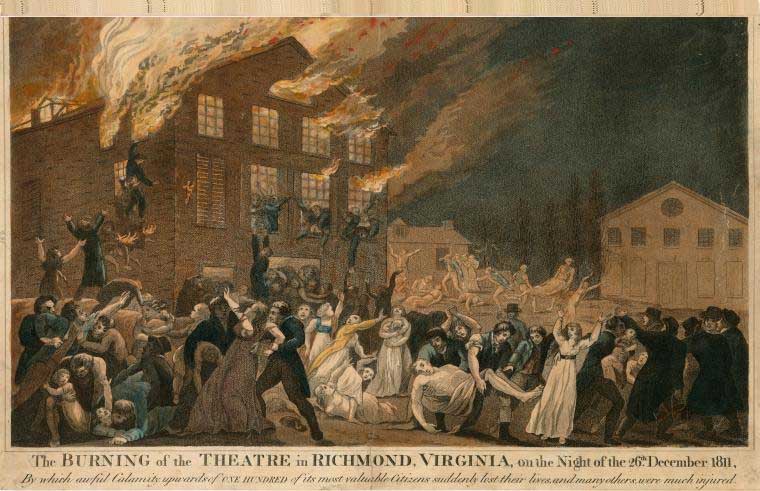

It was on this day, January 19th, in 1812, that the Rev. Dr. Samuel Miller delivered a sermon “at the request of a number of young gentlemen of the city of New-York who had assembled to express their condolence with the inhabitants of Richmond, on the late mournful dispensation of Providence in that city.” A terrible event, the tragedy caught the attention of the young nation, and throughout the Church, not a few pastors addressed themselves to various aspects of the horrible fire. [See a partial list at the end of the sermon text, below.] By way of background, as Dr. Miller himself relates in a note suffixed to his sermon:—

“On the night of December 26, 1811, the theatre in the city of Richmond, Virginia, was unusually crowded; a new play having drawn together an audience of not less than six hundred persons. Toward the close of the performances, just before the commencement of the last act of the concluding pantomime, the scenery caught fire, from a lamp inadvertently raised to an improper position, and, in a few minutes the whole building was wrapped in flames. The doors being very few, and the avenues leading to them extremely narrow, the scene which ensued was truly a scene of horror! It may be in some degree imagined, but can never be adequately described!—About seventy-five persons perished in the flames. Among these were the governor of the State; the President of the Bank of Virginia; one of the most eminent Attorneys belonging to the bar of the commonwealth; a number of other respectable Gentlemen; and about fifty females, a large portion of whom were among the Ladies of the greatest conspicuity and fashion in the city.”

In Dr. Miller’s sermon, the first two major points of his sermon are much more in keeping with what we might expect. However, in his third division of the sermon—the moral application—Miller uses the occasion to speak out against the theatre as an institution. In this, he echoed a common sentiment among Christians of his day, who generally opposed the theatre and the profession of acting.

For those with the time and interest to read, the text of Dr. Miller’s sermon follows.

A SERMON.

Lamentations 2:1,13: How hath the Lord covered the daughter of Zion with a cloud in his anger, and cast down from heaven unto the earth, the beauty of Israel, and remembered not his footstool in the day of his anger! What thing shall I take to witness for thee? What thing shall I liken to thee, O daughter of Jerusalem? What shall I equal to thee, that I may comfort thee, O virgin daughter of Zion? For thy breach is great like the sea; who can heal thee?

THE prophet Jeremiah lived in a dark and distressing day. Religion, among his countrymen, had sunk to an ebb awfully low. The body of the people had become extremely licentious in principle, and corrupt in practice. And a holy God had visited them with many tokens of his righteous displeasure. By fire, by famine, by pestilence, and by the sword, he had taught them terrible things in righteousness; until, at length, wearied with their iniquities, he delivered them into the hands of their enemies, by whom they were, as a people, nearly destroyed.

Over this melancholy scene of guilt and suffering the Prophet composed his Lamentations. And never were scenes of misery, and feelings of anguish, painted with a more masterly hand. Never were the pathos and tenderness, as well as the force of grief, more strongly displayed. As one of the ancient Fathers beautifully expresses it, “every letter appears to be written with a tear, and every word to be the sound of a broken heart; and the writer a man of sorrows, who scarcely ever breathed but in sighs, or spoke but in groans.”

Having been requested, on this occasion, to address my audience with reference to a late awful calamity, well known to you all, which had destroyed many valuable lives, and has covered a sister City with mourning; I have chosen the words just read as the foundation of what shall be offered. May the great Master of assemblies direct us to such an application of them as shall be profitable to every hearer!

How hath the Lord covered the daughter of Zion with a cloud in his anger, and cast down from heaven unto earth, the beauty of Israel! What shall I take to witness for thee? What thing shall I liken unto thee, O daughter of Jerusalem? What shall I equal to thee, that I may comfort thee, O daughter of Zion? For thy breach is great, like the sea; who can heal thee?

Without staying, at present, to explain in detail the several parts of this passage, I shall only observe, that by the daughter of Zion, and the daughter of Jerusalem, we are to understand, by a figure common with this Prophet, the inhabitants of the Jewish capital, in which Zion stood; or rather the Jewish nation, the covenanted people, the visible Church of God, under the Old Testament economy. Of course, what the Prophet applies to that afflicted city, may, without impropriety, be applied either to the whole, or any part of a community, who call themselves a Christian people; or who are embraced even by the most lax profession, within the pale of the visible Church.

We may therefore consider the text first, as a devout acknowledgment of the hand of God, in the afflictions which the Prophet laments;—secondly, as an expression of sympathy with the afflicted;—thirdly, as pointing to the moral application of the calamities which he deplored.

I. There is, in the passage before us, a devout acknowledgment of the hand of God, in the affliction which the prophet laments. How hath the LORD covered the daughter of Zion with a cloud in his anger! How hath the LORD cast down the beauty of Israel!

The doctrine, that the providence of God extends to all events, both in the natural and moral world; that nothing comes to pass without either his direct agency, or, at least, his wise permission and control; is a doctrine not only laid down in the plainest and most pointed manner in scripture; but also one which results from the perfections and the government of God when admitted in almost any sense. If there be a general providence, there must be a particular one. If God govern the world at all, he must order and direct everything, without exception. Yes, brethren, if it were possible for a sparrow to fall to the ground without our heavenly Father; or if it were possible for the hairs of any head to fail of being numbered by the infinite One; in short, if it were possible that there should be anything not under the immediate and the constant control of the Governor of the world; then it would follow that some things may take place contrary to his will; then prayer would be a useless, nay, an unmeaning service; then Jehovah would be liable, every moment, to be arrested or disappointed in the progress of his plans, by the caprice of accident. But, if none of these things can be supposed without blasphemy, then the providence of God is particular as well as universal. It extends to all creatures, and all their actions.—Is there evil in the city and the Lord hath not done it? No; the devouring fire; the overwhelming tempest; the resistless lightning; the raging pestilence; the wasting famine; and the bloody sword, even when wielded by the vilest of men, are all instruments in the hand of God for accomplishing his will and pleasure. And as the providence of God is actually concerned in every thing which befalls individuals or communities; so he requires us to notice and to acknowledge that providence in all his dispensations towards us. Not to regard the work of the Lord, or not to consider the operation of his hands, he pronounces to be sin; and denying his agency in the works of providence, he expressly condemns, as giving his glory to another.

While, therefore, we deplore the heart-rending calamity which had fallen upon a neighboring city, let us not forget, or place out of sight, the hand of God in the awful scene. It was not the work of chance. A righteous God has done it. His breath kindled the devouring flame. Not a spark of the raging element rose or fell without his providential guidance: not a victim sunk under its destroying power, without the discriminating and immediate hand of sovereign Wisdom. He ordered and controlled all the circumstances attending the melancholy scene. He doth not, indeed afflict willingly, nor grieve the children of men. But still affliction cometh not forth of the dust, neither doth trouble spring out of the ground. What! shall we receive good at the hand of God, and shall we not receive evil also? The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord!

II. The Language of the mourning Prophet, while it notices and acknowledges the hand of God in the calamities which it deplores, at the same time expresses the tenderest sympathy for the sufferers. This is indicated in every line of our text and context: and it is the feeling which ought to be cherished upon every similar occasion.

To sympathize with suffering humanity, however that suffering may have been produced, is a dictate of nature, as well as demanded by the authority of our common Creator. Thou shalt weep with them that weep, is a divine precept. When one member of the body suffers, all the members suffer with it. Thus it is in the social as well as in the physical body. Thus it is in domestic society. And thus it ought to be in the large family of a city, a state, or a nation. When one part of a nation is afflicted, all the rest ought to feel for it. When, therefore, any of our friends or neighbors, or any of the most remote portions of the same associated family are visited with any signal calamity, we are bound to consider it not only as a solemn lesson addressed to the whole body; but also as calling upon us to feel for, and sympathize with them; as they, under like circumstances, ought to sympathize with, and feel for us. When this is not the case, one great design of Jehovah’s judgments, which is to instruct and to impress a whole people, by the calamities of a part, is, undoubtedly, speaking after the manner of men, opposed and defeated.

The melancholy dispensation of providence which we this day deplore, is one pre-eminently calculated to interest the feelings, and to excite the tenderest sympathy of very mind. How shall we speak of a scene of such complicated horror? The heart sickens at the dreadful recital! When our beloved relatives die on the bed of disease, the event is solemn, and the bereavement trying; but it is the course of nature; and the frequency of the occurrence disarms it of more than half its terrors. When our friends and neighbors fall in battle, the stroke is painful; but the soldier is expected, by himself and by others, to be in danger of such an end. When those who sail on the mighty deep, are dashed on the rocks, or swallowed up in the merciless waves, we mourn over the catastrophe; but when be bade them farewell, we remembered that they might never return.

But how shall we describe a calamity which has plunged a whole city into agony and tears? A calamity which, to the number and the importance of its victims, added all the circumstances of horror which can well be conceived, to overwhelm the mind! How sudden the burst of destruction! How unexpected its approach, at such a place, and at such a time! What complicated agony, both to the sufferers and to the survivors, attended its fatal progress! But I dare not attempt further to depict a scene from which the mind revolts with shuddering!

Is there a Husband or a Wife who does not feel for those who saw beloved companions writhing in the merciless flames, and sinking in the most dreadful of all deaths, without being able to afford them relief? Is there a Parent who does not feel for those agonizing fathers and mothers, who saw their endeared and promising children torn from them in an hour of unsuspecting confidence and mirth? Is there a Brother or a Sister who does not sympathize with those almost frantic survivors, who were compelled to abandon to their cruel fate relatives dear to them as life? Is there a Patriot who does not feel for the fatal stroke which snatched an amiable and respectable Chief Magistrate from the bosom of a beloved family, and from the confidence of his fellow citizens? Is there a mind capable of admiring the attractive, the interesting, and the elegant, who is not ready to drop a tear over youth, beauty, genius, learning, and active worth, all sinking together in one smoking ruin? Is there a heart alive to the delights of society, and the endearments of friendship, who does not mourn over the melancholy chasm, which has been made in the social circles of that hapless city?—O Richmond! bereaved and mourning Richmond! What shall we say unto thee? How shall we comfort thee? Thy breach is great like the sea; who can heal thee? None but that God who has inflicted the stroke! O that our heads were waters, and our eyes fountains of tears, that we might weep over the slain of the daughter of thy people!

III. We may consider the passage before us as pointing to the moral application of the calamities which it deplores.

We are not only bound, my brethren, to notice and acknowledge the hand of God, in the dispensations of his providence, but also to study the moral aspect of those dispensations, and to apply from time to time the great moral lessons which they inculcate. If one great design of God in all his works of providence, especially in the judgments which he executeth, is to make us feel, and to constrain us to pause in our career of folly, and consider our ways;—then, undoubtedly, we are criminal unless we study to derive, from every remarkable event, the instructive lessons which it is suited to convey. Under this impression I am persuaded, that the Calamity which we lament, ought to be employed, among other purposes as an occasion of entering a solemn protest against a prevailing, but most unchristian and most baneful Amusement.

The finger of God, in that calamity, points to this Amusement, with a distinctness which cannot be mistaken, and with a solemnity which ought to excite our deepest attention!

I am very far, my brethren, from asserting that the calamity to which we refer is to be considered as a special judgment on the immediate sufferers, on account of the unhallowed place and employment in which it found them. And still further am I from daring to pronounce on the character or the eternal state of those who were hurried before the bar of God from that place, and that employment. Alas! when mortals undertake to wield the thunders of Omnipotence, they display more of their own presumption and folly, than of an enlightened zeal for God and holiness. Still, however, when a dispensation of Providence of the most signal kind, stands in mournful connection, as to time and place, with a prevailing sin; and when public feeling, as well as that Providence, opens the way for solemn remonstrance and warning, it were criminal to be silent. As a Minister of Jesus Christ, therefore, and as one bound by his own solemn vows, as well as by the authority of his Master, to be faithful, I dare not permit the present occasion to pass without imparting to you, most unreservedly, my impressions of the theatre as a public amusement.

I am constrained, then, to express my deliberate conviction, that theatrical entertainments are criminal in their nature, and mischievous in their effects; that they are directly hostile to the precepts, and to the whole spirit of the Religion of Jesus Christ; that they are deeply baneful in their influence on society, and utterly improper to be attended or countenanced, by those who profess to be the disciples of Christ, or even the friends of morality.

That this estimate is, by no means, an erroneous or extravagant one will, I trust, be made to appear from the following considerations.

1. To attend on theatrical exhibitions, as an amusement, is a criminal waste of time. I take for granted that this argument will be thought entirely destitute of force, by those children of vanity, who never consider the purpose for which they were sent into the world, or lay to heart the shortness and the infinite value of time. But to the man of spiritual wisdom, who remembers that life is short; that there is much to be done; that he has never yet done, either for God or for his generation, a tenth part of what he might and ought to have performed; and that for the manner in which we spend every hour, we must speedily give an account before the judgment seat of Christ; to every one who remembers these things, the argument will carry with it irresistible force. To spend an hour unprofitably, or even in a less profitable way, when a mode of spending it more conformably to the will of God, and more usefully to himself and others, is within his reach, will appear to such an one quite as criminal as many of what are called gross sins, and quite as sacredly to be avoided.

The design of recreation,—I mean the design of it in the view of the Christian, or even of the sober minded votary of mere natural religion, is not to kill time; but to refresh the body and mind, and to prepare them for the more vigorous and comfortable performance of duty. It follows, therefore, that recreations are lawful only so far as they are necessary and suitable for this purpose; of course, when they are either carried to such a length as to consume more time than we need to employ in this manner; or when they are of such a nature as to have no tendency to prepare either the body or the mind for the more easy, comfortable, and perfect discharge of the sober duties of life, but the contrary, they become wholly unjustifiable. They are a criminal waste of time; and to indulge in them is utterly unsuitable to the character of rational and accountable beings.

Let us apply these principles to an attendance on the theatre as an amusement. Can any of the patrons of this amusement lay their hands on their hearts, and say, in the presence of God, that they attend upon it merely, or even chiefly, for the purpose of preparing their minds and bodies for a more suitable discharge of their duties as moral and accountable beings! Can they say that it is better calculated, than any other within their reach, to prepare them for the conscientious discharge of those duties? And can they appeal to the Searcher of hearts, and declare, that four, five, or six hours in an evening, devoted to preparation for this amusement and attendance upon it, is no more time than is necessary to refresh and invigorate them for the sober and all-important work for which they were sent into the world? The most determined advocate of the theatre that lives, will not dare to answer these questions in the affirmative. He would blush at the thought of applying such principles to his practice. Either then the scriptural precept to redeem time, and the scriptural rules for disposing of time, must be utterly rejected; or theatrical amusements must be pronounced criminal. Either men are not accountable for the manner in which they spend their time; or it is a sin to squander precious hours in amusements, of which the lightest censure that can be passed upon them is, that they are unprofitable and vain.

2. But we may go further; theatrical entertainments are not merely unprofitable; not merely a waste of time, which, if nothing more could be said, would be sufficient to condemn them; but they have also a direct and unavoidable tendency to dissipate the mind, and to lessen, if not destroy, all taste for serious and spiritual employments. Let me appeal to every one who has been in the habit of attending on them, whether they are not directly hostile to the spirit of prayer, and to a life of communion with God? Is there not something—I speak now of the most decent plays—is there not something in the sentiments uttered in the theatre; in the scenery displayed; in the dress, attitudes, and deportment of the performers; and in the licentious appearance, and libertine conduct of many of the audience, which is calculated, to say the least, to expel seriousness from the mind; to drive away all thoughts of God, of eternity, and of a judgment to come; and to extinguish all taste for spiritual services? Did ever an attendant on the theatre feel a cordial relish for the devotions of the closet, or of the family, immediately after his return from that place of amusement? I need not wait for an answer. There is no one who ever beheld the assemblage of “dazzling vanities” there displayed, who is not perfectly ready to pronounce, that few things have a more direct tendency to give the mind a vain and frivolous cast; to impair a taste for devotion; and to lessen, if not entirely banish, that spirituality which is at once the duty and the glory of the Christian.

Here I might rest the weight of the argument: for that which has a tendency to make the mind vain and frivolous must be criminal. That which has a tendency to draw off the heart from the sober, the solid, the useful, and the pious; and to inspire it with a ruling passion for the gay, the airy, the romantic, and the extravagant, cannot fail of being deeply pernicious. What a late eloquent writer says on another subject, is strictly applicable to this. The theatre “does not instruct a man to act, to enjoy, and to suffer, as a being that may tomorrow have finally abandoned this orb. Every thing is done to beguile the feeling of his being a stranger and a pilgrim on the earth.” The great end of all its art is “to raise the groves of an earthly paradise, to shade from sight that vista which opens into eternity.” But this is not all: for,

3. The theatre is now, and ever has been, a school of false sentiment, and of licentious practice. While even the few plays which may be called decent have a tendency to impart to the mind a vain and dissipating influence; a much larger number produce a more deep and extensive mischief. By far the greater part of the most popular dramas are profane, obscene, and calculated to pollute the imagination, to inflame the passions, and to recommend principles the most pernicious, and practices the most corrupt. How common is it to find in the language of the theatre, the most unqualified profaneness, and even blasphemy! How often are mock prayers, and irreverent appeals to the Majesty of heaven, exhibited on the most trivial occasions! How often is the dialogue interspersed with terms and allusions which pain the ear of modesty; and these pronounced and exhibited in a way calculated to give additional force to the evil! and are such exhibitions innocent? Are they such as a disciple of Christ can witness with safety, or countenance with a good conscience? If they are, then it is difficult to say what is criminal, or what may not be justified.

But in a large number even of those plays which are not chargeable with open profaneness, or indelicacy of language, the moral is such as no friend of religion, or of human happiness, can approve. Piety and virtue are made to appear contemptible; and vice, in the person of some favorite hero, is exhibited as attractive, honorable, and triumphant. Folly and crime have palliative, and even commendatory names bestowed upon them; and the extravagance of sinful passion is represented as amiable sensibility. The good man of the stage is a character as opposite to the good man of the Bible, as light to darkness, of as Christ to Belial. The almost universal maxims of the theatre are, “that love is the grand business of life: that present gratification is to be preferred to suffering virtue; that ambition is superior to contentment; that pride is necessary to carry a man with decency through the world; that revenge is manliness of spirit; that patience is meanness; that humility is degradation; that forgiveness of injuries is beneath a gentleman; that human opinion is the strongest motive of action; that human praise is the highest reward; that human censure is to be deprecated more carefully than the wrath of God; that dueling is unavoidable; that self-murder may be justified; that conjugal infidelity is a venial, if not an amiable frailty; and that, provided a man be frank, generous, and brave, he may be a libertine, and invader of conjugal purity, a despiser of God and a trampler on his laws, and yet celebrated as the possessor of an excellent heart.” Yes, my brethren, very often, nay, almost continually, are plays not only exhibited in this Christian city, but received by thousands, with bursts of applause, which convey, and directly or indirectly recommend, sentiments no less exceptionable and pestiferous than these!

But, let me ask, are sentiments and representations such as these, reconcilable with the Gospel of Jesus Christ? Are they friendly either to individual happiness, or social order? Are they proper for Christians to witness or to encourage? Are ribaldry, blasphemy, and indirect commendations of sin, proper even for decent ears? Is this a school to which we ought to be willing to introduce our sons and daughters, even if we had no higher aim than to prepare them for virtuous, dignified, and useful action in the present life? Alas! it is humiliating to be driven to the necessity of asking these questions; but it is still more humiliating to see thousands who profess to be Christians, acting as if they might be deliberately answered in the affirmative!

4. Once more; those who attend the theatre support and encourage a set of performers in a life of vanity, licentiousness and sin. What is the life of Players? Even in its best form, and when not degraded by uttering or exhibiting anything directly immoral, it is submission to a course of mean and unworthy personation for the entertainment of the multitude. But it is in fact, much worse than this. A large portion of their time is employed in personating, displaying, and recommending vice. It were easy, moreover, to show, that the constant habit of acting a part; the practice of personating characters the most profligate and vile, much more frequently than those of an opposite cast; together with the nature of the intercourse which takes place, and must take place, between performers on the same stage, all have a tendency to corrupt morals. Were the purity both of their principles and practice to be maintained under circumstances such as these, it would be almost a miracle. Accordingly, in perfect correspondence with their employment, is their prevailing character. In all countries under heaven they are found, what, upon principles of philosophy, as well as religion, we might expect to find them, triflers, buffoons, sensualists, unfit for sober employment, regardless of religion, and loose in their morals. It is not pretended that there have been no exceptions to this character. But the exceptions have been so few, and their circumstances so peculiar, as to confirm rather than invalidate the general argument. And is it even true, that there ever have been complete exceptions? Was there ever a player who exhibited a life of steady, exemplary piety? Was there ever a theatrical performer, even of the greatest talents, who enjoyed the respect and confidence of any community? Nay, has there not been, in all ages, and in all states of society, a sort of infamy attached to the professions? Yet this is the profession which all who frequent the theatre contribute their share to encourage and support. They are chargeable with giving their influence and their pecuniary aid, for the maintenance of a class of persons, whose business it is, indirectly, to recommend error and crime, to corrupt our children; and to counteract whatever the friends of religion and good morals are striving to accomplish for the benefit of society.

If this representation be just; if attending on the theatre is a criminal waste of time; if it tends to dissipate the mind and to render it indisposed for serious and spiritual employments; if theatrical exhibitions are, very often to say the least, indecent, profane, and demoralizing in their tendency; and if their patrons, by every attendance on them, encourage and support sin, as a trade; then I ask, can any man who claims to be barely moral,—placing piety out of the question,—can any man who claims to be barely moral, conscientiously countenance such a seminary of vice? Above all, can a disciple of Jesus Christ, who professes to be governed by the Spirit, and to imitate the example of his Divine Master; who is commanded to live soberly, righteously, and godly in this present world; who is required to pass the time of his sojourning here in fear; who is warned not to be conformed to the world, and to have no fellowship with the unfruitful works of darkness, but rather to reprove them; who is required to deny himself, to crucify the flesh with the affections and lusts, and whether he eats or drinks, or whatever he does, to do all to the glory of God;—can a disciple of Jesus Christ, who is commanded to shun the company of the profane, to avoid the very appearance of evil, and to pray, Lead us not into temptation,—can he be found in such a place without sin? Is the theatre an amusement in the immediate prospect of which any man can go to the throne of grace, and implore a blessing? Is the theatre an amusement which will be remembered with complacency by any man when he comes to die? Or is it a place from which any reflecting man would be willing to be called to the bar of God? These are questions which, I take for granted, some of my hearers will receive with a smile; but which I most affectionately entreat those who have named the name of Christ to ponder in their hearts.

I am aware that, to this view of the subject, many objections will be made. It will be confidently asked, “Are there not some correct and moral plays, from which noble sentiments may be learned? Why, then, condemn theatrical entertainments in the gross?” I answer, allowing, for argument sake, that there are some unexceptionable, nay even excellent plays; allowing that one in twenty (an allowance much beyond the truth) is of this character; is it wise, is it lawful, to administer more than a pound of poison, for the sake of conveying with it an ounce of nourishment? Besides, we are not to judge of the theatre by the character of a single play, or by the merits of a single actor. We are to contemplate and to decide upon it as a system; and that, not as it might be supposed to be, but as it actually exists. And if its general characteris, and in all ages and nations has been, corrupt and mischievous, then the argument which pleads in its favor, on account of the small portion of just sentiment and real decency which it may exhibit, is as weak in logic as it is detestable in morals.

“But persons,” it will be said, “as pious as the preacher, or any of those who condemn it, have gone to the theatre; undoubtedly, then it cannot be a very immoral place of resort.” And so persons more pious, perhaps, than the preacher, or any of his hearers, have committed, what are acknowledged on all hands to be sins, and sometimes even gross sins: but do they cease to be sins, because pious men have committed them? Alas! brethren, how long will men deceive themselves by taking the example of fallible mortals, and the fashion of the world, instead of the Word of God as their guide? It is not denied, that professing Christians very often, and real Christians sometimes, may have been found in the theatre: but we insist upon it, that all such cases ought to be regarded precisely in the same light, as when professing, or real Christians, fall into the commission of any other sin; that is, with total disapprobation of their conduct, as unworthy of the name which they bear; and with humiliation and mourning, as injurious to the honor of religion. It is not what this or that professor does, that will be asked of us, or that will be the rule of proceeding, before the judgment seat of Christ. To the law, and to the testimony; if they speak not according to this word, it is because there is no light in them.

“But the play-house never injured me,” another advocate of this amusement may plead “My principles are so firmly fixed, and my mind so well balanced, that I can attend upon it, at least now and then, without the smallest sensible injury. In me, therefore, it can be no sin; especially as I go but seldom, and then only to see a good play.” When persons discover so much confidence in their own strength, as to imagine, that they alone, of all the children of men, may safely trifle with temptation, and tamper with sin, they give the worst possible evidence of the fact being really so. As a general rule, we are never so much in danger of moral mischief, as when we presumptuously imagine that we are totally beyond its reach. But allowing it to be as they say; they ought to remember, that “if they can venture into the fire with safety, there are others who cannot.” If they can attend theatrical exhibitions without injury, thousands of the young, whose principles are unfixed, and whose characters are unformed, go at the peril of their perdition. If they have no reason to apprehend danger, they encourage, by their example, multitudes, who have every reason to apprehend the utmost danger. If they go but seldom, and then only to good plays, they give the sanction of their presence to others, who will go often, and to plays of all descriptions. And is this to be justified in persons who live in society, and who are bound habitually to regard the welfare of society? The truth is, my brethren, whatever may be the harmlessness of the theatre to particular individuals, who frequent it, they encourage by their example, and help to support by their money, that which is a source of corruption to thousands. In fact, no person can contribute, in the smallest degree, to the support of the stage, either by his presence or his purse, without being more or less, a partaker in all the sin, and an accessory to all the mischief which may be transacted there.

“But certainly,” another class of objectors will say, “attending the theatre, though allowed to be, in a degree, improper, is not so criminal as some other practices, in which the mass of mankind, and more particularly the inhabitants of great cities, will always indulge. Is it not advisable, therefore, to countenance, or at least to tolerate this, as a less evil than many others? Especially when it is recollected, that there is something in theatrical entertainments more refined, more intellectual, and more elevated, than in almost any other that can be imagined.” This precisely, in principle, as if any one were to say, “Swearing and lying, sabbath-breaking and drunkenness, are none of them so atrocious in their nature as murder; and, therefore, when we see men in danger of committing the last mentioned crime, we ought to endeavor to divert them from it, by persuading them to engage in the practice of the former sins.” But I need not say, that such reasoning and such counsel would be abhorred by every correct mind. It is not for us to attempt to balance known sins against each other. Whether attending the theatre be, in its own nature, and in the sight of the heart-searching God, more or less criminal than many of those transgressions of the divine law which we are accustomed to call gross sins, is a question which I dare not decide, because I do not know. This, however, I know, that if it be a sin at all, it ought to be abhorred and avoided. It is never justifiable to make a compromise with sin. It is always criminal to do evil that good may come.

With respect to the plea that theatrical entertainments have a refined and intellectual character which recommends them to the more intelligent part of society, it does not weaken, in the least degree, the preceding course of reasoning. The fact under certain qualifications, is not disputed. Oratory is doubtless, a great and, in itself, most respectable art. Even the mimickry of it has wonderful charms; and therefore, when dramas of the better sort are represented with that exquisite skill and force which have sometimes appeared on the stage, they certainly form an amusement which is less gross and frivolous than many others, and which more particularly addresses itself to the intellectual powers, and to a literary taste. All this may be freely granted; and yet, if the theatre is now, always has been, and from the nature and design of the amusement, must ever be, a system of deep, wide-spreading, and incalculable corruption; is it not the duty of every one who values the welfare of society, to deny himself a favorite gratification, rather than to encourage so great an evil? Nay, the more plausible and fascinating the amusement, the greater its danger, when it draws such consequences in its train; and, of course, the greater the sin of giving it encouragement. And let that person who acknowledges the theatre to be a corrupting and criminal amusement, and who, at the same time, suffers himself to be drawn thither by the fame of a celebrated actor, or by what he calls a taste for the exhibition of talents;—let him know, and tremble at the thought, that he is practically declaring, that his taste is to be indulged at the expense of the most precious interests of society, and at the risk of the everlasting displeasure of his God!

But it will, probably, still be demanded, “Why single out the theatre from all other sins, and hold it up with this reiterated and marked reprobation? Is it so much worse than other evils, as to be worthy of such peculiar and unrelenting censure?” I answer, we recur to the subject the more frequently, and raise our warning voice against it, with the more emphasis, for two reasons. The first is, because we are verily persuaded, that the mischiefs of this amusement are by no means so limited and unimportant in their extent, as many, who acknowledge its sinfulness in general, are ready to imagine. We are persuaded that, estimating its immediate and its ultimate consequences; considering the close connection in which it stands with many other sins, the mass of evil to which it gives rise, is so great as to defy calculation. The second reason is, that, by some strange concurrence of circumstances, it has happened that this evil, criminal and pestiferous as it evidently is, has crept, under a sort of disguise, into the Church of Christ, and has come to be considered as a lawful amusement for Christians! With respect to most other sins, which we are in the habit of reproving, they are freely and generally acknowledged to be such; and when any of those who profess to be Christians fall into them, the propriety of admonishing, suspending, or excommunicating the offenders, as the case may be, is acknowledged by all. But we have here the strange phenomenon of a great and crying sin, which professing Christians not only indulge, but which they openly vindicate; to which they freely and publicly introduce their children; and, as if this were not enough, in behalf of which they take serious offence when the Ministers of Christ venture to speak of it in the terms which it deserves! It has been often said, that Christians are most in danger from things lawful. It is certain that there is often more danger from things esteemed lawful, than from those of which the iniquity is known and undisputed. We are constrained, then, to dwell the more largely, and to remonstrate the more solemnly, on the sin under consideration, because we are confident it is not understood; because we are verily persuaded that a considerable portion of professing Christians need instruction, as well as warning, on the subject; and because we cherish the hope that nothing more than further light is necessary to induce thousands, who now rank among the patrons of the theatre, to forsake it with indignation.

I am perfectly sensible that all this will be called by some, “the dark and scowling spirit of Calvinism;” that it will be stigmatized as “the cant of that puritanical austerity, which aims at being righteous overmuch.” And is it come to this, my brethren, that when the plainest demonstration, drawn from the word of God, and from the essential principles of morals, cannot be answered by argument, it is to be assailed by the pitiful weapons of sneer and abuse? Answer me one plain question. Does the representation which has been made, comport with God’s word, or does it not? If not, reject it without hesitation. But if it does, then reject it at your peril! If it does, then, believe me, no man will gain anything by loading it with contemptuous epithets. It does comport with that word! It is the truth of God! It is such Calvinism; it is such Puritanism, as will be found to stand the trial of the Great Day; when all those miserable apologies, and unscriptural subterfuges, in which multitudes who call themselves Christians, now take shelter, shall be covered with shame and contempt.

But is it a fact that the doctrine which condemns the theatre, as an immoral and criminal amusement, is an austerity confined to the advocates of a particular creed? No, brethren; you ought to know that theatrical amusements have been unequivically condemned, by the decent, and the virtuous part of society, in all ages. You ought to know, that even pagans, and Christians of all denominations, and in every period of the Church, have united in denouncing this class of amusements, as essentially corrupt and demoralizing in their nature. The following extracts will fully establish this position.

Plato tells us, that “plays raise the passions, and pervert the use of them; and, of consequence, are dangerous to morality.” For this reason he banished them from his commonwealth. Aristotle lays it down as a rule, “that the seeing of comedies ought to be forbidden to young people; such indulgencies not being safe, until age and discipline have confirmed them in sobriety, fortified their virtue, and made them proof against debauchery.” Tacitus informs us, that the “German women were guarded against danger, and preserved their purity, by having no play-houses among them.” And even Ovid, in his most licentious poems, speaks of the theatre as favorable to dissoluteness of principle and manners; and, afterwards, in a graver work, addressed to Augustus, advises the suppression of this amusement, as a grand source of corruption.

In the primitive Church, both the players, and those who attend the theatre, were debarred from the Christian sacraments. All the Fathers, who speak on the subject, with one voice attest that this was the case. A number of the early Synods or Councils, passed formal canons, condemning the theatre, and excluding actors, and those who intermarried with them, or openly encouraged them, from the privileges of the Church. The following declarations of Theophilus, pastor of Antioch, an eminent divine, who lived in the second century, are too pointed and appropriate to be omitted. “It is not lawful for US (Christians) to be present at the prizes of your gladiators, lest, by this means, we should be accessory to the murders there committed. Neither dare we take the liberty of attending on your other shows, lest our senses should be polluted and offended with indecency and profaneness. We dare not see any representations of lewdness. They are unwarrantable entertainments; and so much the worse, because the mercenary players set them off, with all the charms and advantages of speaking. God forbid that Christians, who are remarkable for modesty and reserve, who are bound to enforce self-discipline, and who are trained up in virtue, God forbid, I say, that we should dishonor our thoughts, much less our practice, with such wickedness as this!”

Almost all the reformed Churches have, at different times, spoken the same language, and enacted regulations of a similar kind. The Churches of France, Holland, and Scotland, have declared it to be “unlawful to go to comedies, tragedies, interludes, farces, or other stage plays, acted in public or private; because, in all ages, these have been forbidden among Christians, as bringing in a corruption of good manners.” Surely this concurrence of opinion, in different countries, expressed not lightly or rashly, but as the voice of the whole Church, ought to commend, at least the respectful attention, of all who remember how plain and how important is the duty of Christians to follow the footsteps of the flock.

To these authorities it may not be useless to add the judgment of a few conspicuous individuals, of different characters and situations, all of whom were well qualified to decide on the subject: individuals, not of austere or illiberal minds, and who have never been charged with the desire of contracting to an unreasonable degree the limits of public or private amusement.

Archbishop Tillotson was neither a Calvinist nor a Puritan; yet he, after some pointed and forcible reasoning against it, pronounces the play-house to be “the Devil’s chapel;” a “nursery of licentiousness and vice;” “a recreation which ought not to be allowed among a civilized, much less a Christian people.” Bishop Collier was very far from being either a Calvinist or a Puritan; yet he solemnly declares, in the preface to a learned and able volume which he wrote against the theatre, that he was “persuaded nothing had done more to debauch the age in which he lived, than the stage poets and the play-house.” Sir John Hawkins was never considered as over-rigid or illiberal; but we find him speaking of the theatre in this pointed and unequivocal language: “Although it is said of the plays, that they teach morality; and of the stage, that it is the horror of human life; these assertions are mere declamation, and have no foundation in truth or experience. On the contrary, a play house, and the regions about it, are the very hotbeds of vice.” Nay, even the infidel philosopher, Rousseau, in opposing the establishment of a theatre at Geneva, speaks of it in the following manner: “It is impossible that an establishment so contrary to our ancient manners can be generally applauded. How many generous citizens will see with indignation this monument of luxury and effeminacy raise itself upon the ruins of our ancient simplicity! Do you think they will authorize this innovation by their presence, after having loudly disapproved it? Be assured that many go without scruple to the theatre at Paris, who will never enter that of Geneva, because the good of their country is dearer to them than their amusement. Where would be the imprudent mother who would dare to carry her daughter to this dangerous school; and how many respectable women would think they dishonored themselves in going there! If some persons at Paris abstain from the theatre, it is simply on a principle of religion; and surely this principle will not be less powerful amongst us, who shall have the additional motives of morals, of virtue, and of patriotism; motives which will restrain those whom religion would not restrain.”

I have thus, my brethren, endeavored, I trust in the fear of God, to discharge a duty which my office, and the present occasion, have laid upon me. It has been my aim to speak the truth in love. If one word of a contrary kind has escaped me, I heartily wish it unsaid. But if, as I verily believe, what you have heard is the unexaggerated truth, may the Holy Spirit impress it on every heart! Brethren, the subject is a serious one! If the half of what has been told you concerning the theatre is true, then not only every professing Christian, but every father of a family, every good citizen, every friend to social order and happiness, ought to set his face against it as a flint, and discountenance it by all fair and honorable means. But, to such of you, my hearers, as profess to be followers of Jesus Christ, I address myself with especial confidence. Can you,—if you believe the foregoing statement,—can you, after this, ever set your feet within the walls of a theatre? I do not ask whether you can go often, but can you go at all? It is impossible for me to conceive how you can venture, without previously coming to the conclusion, that the morality of the Bible is too rigid and austere for you. But will you venture to adopt this conclusion? No, you dare not. To do so, would be to seal the death-warrant of your Christian character. Brethren, I repeat it, the subject is a serious one! You may apologize and evade; you may secretly complain about the “strictness,” and “austerity;” you may plead the current of fashion, and the habits of those around you, as much as you please: but the question is short; Will you obey God rather than man, or the reverse? Will you take the scriptures, or the maxims of a corrupt world for your guide? I leave it with your consciences and your God!

The remainder of this discourse will be addressed to the younger part of my audience.

In undertaking this service, my young friends, one of the most pleasing hopes that occurred to my mind, was, that God might bless it to some, at least, of your number. It is delightful to preach to the young! When we address the aged, or even those who have passed the meridian of life, and who have lived all their days in carelessness and sin, our hopes are comparatively small. The Spirit of God may, indeed, carry home to their hearts the word of his grace. But they have so long resisted and grieved that Spirit, that our prospect of success, speaking after the manner of men, is alas! awfully gloomy. But to admonish the young; to counsel those who have not yet become hardened by inveterate habits of iniquity; and to warn the tender and the inexperienced against the errors, the excesses, the false hopes, and the numberless dangers to which they are exposed; as they are among the most important, so they are also among the most hopeful and pleasant parts of our office. Happy, happy indeed, shall I be, if this service should prove the means of leading even one young person to serious consideration; to embrace that wisdom which is profitable unto all things, having the promise of the life that now is, and of that which is to come!

Let me remind you, my young friends, that you live in an age, and in a city [i.e., New York] peculiarly ensnaring to youth. The delusions of infidelity; the allurements of criminal pleasure; the arts of vain companions; and the fascinations of diversified amusements, present on every side much to dazzle and to deceive; much from which you are hourly in danger. And, alas! how many youth, endowed with talents which might have done honor to religion, to their parents, and to themselves, are daily falling victims to these temptations, and sinking into infamy and destruction! Shall we have the mortification, my young hearers, to see any of you among these wretched victims? God forbid! Our heart’s desire and prayer is, that, despising equally the dreams of false principle, and the pollutions of licentious practice, you may be followers of them who serve their generation by the will of God; and who, through faith and patience, inherit the promises!

Although the occasion has led me to speak particularly by of one kind of amusement, to which the young of the present day are lamentably addicted; yet the same reasoning will apply, with no less force, to a number of others, to which you are equally exposed. I cannot stay, at present, to detail these, or to reason upon them. But whatever amusements, no matter how fashionable, or how strongly recommended they may be, whatever amusements have a tendency to produce dissipation of mind, to lead it away from God, and to impair a relish for spiritual employments; whatever amusements cannot be begun and ended with prayer, and are hostile to a life of communion with the Father of your spirits, and his son Jesus Christ,—are criminal, are mischievous, and, of course, are to be avoided by all those who desire to be really wise, either for this world, or that which is to come.

Let no young person say, “All this reasoning might properly and strongly apply to us were we professors of religion. Those who are such, we acknowledge, are bound to act upon this plan; but WE make no profession, and, consequently, are not thus bound.” And is it, then, no sin for any but professors of religion to waste their time; to indulge in vanity and dissipation; to encourage obscenity, profaneness, and contempt of the gospel; and to give their influence to the support of iniquity as a trade? Is it no sin for any but professors of religion to walk in the way of their hearts, and in the sight of their eyes, fulfilling the desires of the flesh and of the mind; and to be lovers of pleasure more than lovers of God? Alas! there cannot be a greater delusion! We are all under obligations in the sight of God, anterior to any act of profession on our part. Whatever, then, is a sin in a professor, is a sin in any other person. Yes, my young friends, whether you are professors of religion or not, you are rational creatures; you have immortal souls; you are under a holy law; you are hastening to the bar of God; and, as such, in the name of the Master whom I serve, I put in his claim to your affections and your services. As such, I charge you, by all that is glorious in God; by all that is tender in redeeming love; by all that is precious in the hopes of the soul; and by all that is solemn in eternity; that you renounce every thing that is hostile to the service of Christ; and that you make it your study to glorify him in your bodies, and in your spirits which are his.

To such of my young hearers as have urged me to the performance of this service, let me especially say, Another voice, speaking through a catastrophe of the most heart-rending nature, has proclaimed, that the theatre, and all that train of unhallowed pleasures, to which the young are so much attached, are madness and folly! Will you not hear this voice and lay it to heart? If, after all that has lately passed; if, after having your attention seriously drawn to this subject, both by the providence and the word of God; if, after the part you have taken in the exercises of this day, you are still found incorrigibly devoted to those pleasures—allow me affectionately to say—you will have no cloak for your sin. You will have reason to fear the special and destroying judgments of God. For they that being often reproved, harden their necks, shall suddenly be cut off, and that without remedy.

But remember my young friends, that something more is necessary to form a Christian than mere abstinence from what are called criminal pleasures. You may keep at the greatest distance from all of them; you may be models of the industry, the temperance, and the sobriety, which constitute the orderly citizen; and yet be far from the kingdom of heaven. Remember, that, except a man be born again he cannot see the kingdom of God. Remember, that unless you receive Christ, by a living faith, as your Prophet, Priest, and King, and study to walk in him, in all holy obedience, you are Christians only in name. It is the religion which dwells in the heart, and which controls, adorns, and sanctifies the life, that I recommend to your choice. With this religion, and this alone, you will be happy in yourselves, and a blessing to others. With this religion, you will be prepared to enjoy prosperity with comfort, and to meet adversity with resignation. With this religion, you will be able to contemplate death without alarm, and to rejoice in hope of the glory of God.

Beloved youth! the hope of your parents, and of the church; seek this religion. Give neither sleep to your eyes, nor slumber to your eye-lids, until you can, on good grounds, call it your own. To the grace of the Saviour we commend you. May he give you to experience the light of his countenance, and the joys of his salvation! May he teach you how to live, and how to die! May he guide you by his counsel, and afterwards receive you to glory!

AMEN.

Sermons—

Alexander, Archibald, A discourse occasioned by the burning of the theatre in the city of Richmond, Virginia, on the twenty-sixth of December, eighteen hundred and eleven : by which awful calamity a large number of valuable lives were lost. Delivered in the Third Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia, on the eighth day of January, 1812, at the request of the Virginia students attached to the medical class, in the University of Pennsylvania,

Dana, Joseph, Tribute of sympathy : a sermon, delivered at Ipswich (Mass.) January 12, 1812, on the late overwhelming calamity at Richmond in Virginia.

Dashiell, George, A sermon occasioned by the burning of the theatre in the city of Richmond, Virginia on the Twenty-sixth of December, 1811, by which disastrous event more than one hundred lives were lost …

Lloyd, Rees, The Richmond alarm : a plain and familiar discourse in the form of a dialogue between a father and his son : in three parts … : written at the request of a number of pious persons.

Miller, Samuel, A sermon, delivered January 19, 1812, at the request of a number of young gentlemen of the city of New-York who had assembled to express their condolence with the inhabitants of Richmond, on the late mournful dispensation of Providence in that city.

Mordecai, Samuel, A discourse delivered at the synagogue in Richmond on the first day of January, 1812, a day devoted to humiliation and prayer, in consequence of the loss of many valuable lives, caused by the burning of the theatre, on the 26th December, 1811.

Sabin, Elijah R., A discourse preached on Tuesday, February 11, 1812, in presence of the supreme executive of Massachusetts, by request of the young men of Boston, commemorative of the late calamitous fire at Richmond.

Other descriptive materials—

Akers, Bryan, Graphic description of the burning of the Richmond Theatre : December 26, 1811 : compiled from the lips of eye-witnesses (1879).

Broadside: Theatre on fire. Awful calamity! (Richmond, Va., 1810-1811), Broadside. illus. 23 x 18 cm. Within mourning border, printed in two columns divided by heavy single line./ Woodcut of burning house at head of text./ At head of text: A letter from Richmond, Virginia dated Dec. 27, says, “Last night the theatre took fire and was consumed, together with about 80 people …”/ First line: Oh! what a painful, dreadful talk.

Goode, James Edwin, Full account of the burning of the Richmond theatre, on the night of December 26, 1811 (Richmond, J.E. Goode, 1858), 71pp.; 1 illus.; 21cm.

Merritt T. Cooke Memorial Virginia Print Collection, 1857-1907, Archival Material 80 (ca.) items. Include lithographs, engravings, etchings, and watercolors, 1857-1907, of scenic and historic Virginia sites, including several of Virginia churches, Richmond, including one of the burning of the Theatre (1811)…

Tags: Geneva, Ipswich Mass, Jesus Christ, LORD, LSM, Paris, Presbyterian Church, Providence, Third Presbyterian Church

No comments

Comments feed for this article