James Benjamin Green was born on May 10, 1871 to parents Curtis and Sarah Hammond Green, and died on September 8, 1967, at the age of 96. He had received his education at the Peabody Teachers College, Nashville, TN (1889-1891) and the University of Nashville (1891-1893, BA), with postgraduate work there, (1895-96), followed by his preparation for the ministry at the Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, Virginia, 1898-1901.

James Benjamin Green was born on May 10, 1871 to parents Curtis and Sarah Hammond Green, and died on September 8, 1967, at the age of 96. He had received his education at the Peabody Teachers College, Nashville, TN (1889-1891) and the University of Nashville (1891-1893, BA), with postgraduate work there, (1895-96), followed by his preparation for the ministry at the Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, Virginia, 1898-1901.

He was both licensed and ordained in 1901 by Columbia Presbytery, and installed as pastor of the Frierson Memorial Presbyterian church in Columbia, Tennessee, serving there from 1901 through 1903. He then answered a call to serve as pastor of the church in Fayetteville, TN, 1903-1907. His third pulpit and longest pastorate was with the Presbyterian church in Greenwood, SC, where he labored from 1908 to 1921. From this pulpit he was then called to serve as professor of Systematic Theology at the Columbia Theological Seminary, 1921-1950. Announcing his intent to retire in 1946, he was that same year elected to serve as Moderator of the General Assembly (PCUS). Other honors awarded during his life included the Doctor of Divinity degree, conferred by the Presbyterian College of South Carolina (1914) and the Doctor of Letters degree, conferred by Southwest College (1940).

It was on this day, August 14, 1957, that The Southern Presbyterian Journal published an article by Dr. Green on the subject of baptism, which we take the liberty of reproducing here in full. Demand for the article was such that the Journal saw fit to issue it in tract form, publishing at least four editions in the years that followed. While this might be a longer post than you care to read right now, it would certainly be worth printing and filing away for future use.

WHY WE BAPTIZE BY SPRINKLING

by Rev. J. B. Green, D.D.

Columbia Theological Seminary Decatur, Ga.

We differ from our immersionist friends not only in our view of the mode, but also in our view of the meaning of baptism. They think that baptism points to the death, burial, and resurrection of Christ. We object to that interpretation:

Because it is generally agreed that the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper refers to the death and resurrection of Christ. If baptism also signifies the death and resurrection of Christ, then we have two Sacraments which are signs and symbols of the same facts of the life of Christ. Why this double representation of these facts? In that case we have no sign and symbol of the work of the Holy Spirit. In the Old Testament it was not so. There the passover pointed to the work of Christ, but circumcision pointed to the work of the Holy Spirit. For circumcision meant the putting away of carnality, the removal of the sinful flesh. This is the peculiar work of the Holy Spirit. Baptism means the same thing; it means the washing away of sin. We object to the immersion- ist’s view of the meaning of baptism for another reason. The burial of Christ has no redemptive value. Christ would have saved the world if he had not been buried. Why should a rite be ordained to signify a fact which is not essential to the accomplishment of salvation?

Because it is generally agreed that the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper refers to the death and resurrection of Christ. If baptism also signifies the death and resurrection of Christ, then we have two Sacraments which are signs and symbols of the same facts of the life of Christ. Why this double representation of these facts? In that case we have no sign and symbol of the work of the Holy Spirit. In the Old Testament it was not so. There the passover pointed to the work of Christ, but circumcision pointed to the work of the Holy Spirit. For circumcision meant the putting away of carnality, the removal of the sinful flesh. This is the peculiar work of the Holy Spirit. Baptism means the same thing; it means the washing away of sin. We object to the immersion- ist’s view of the meaning of baptism for another reason. The burial of Christ has no redemptive value. Christ would have saved the world if he had not been buried. Why should a rite be ordained to signify a fact which is not essential to the accomplishment of salvation?

We think that baptism represents the work of the Holy Spirit. Why do we so think? For several reasons. There are three Bible symbols of the Holy Spirit. One is oil. In 1 Samuel 10:1-6 we have an account of the anointing of Saul by Samuel, setting him apart to the Kingship. The oil was poured on Saul’s head, and in connection with that anointing the Holy Spirit came upon him.

In I Samuel 16th chapter we have an account of the anointing of David by Samuel. The oil ’ was poured upon David’s head and the Spirit came upon him. These passages indicate that the anointing with oil is typical of the anointing with the Holy Spirit.

Another symbol of the Spirit is water. In Ezekiel 36:25-27, the Lord Jehovah says, “I will sprinkle clean water upon you, and ye shall be clean: from all your filthiness, and from all your idols, will I cleanse you . . . And I will put my spirit within you, and cause you to walk in my statutes, and ye shall keep mine ordinances, and do them.” The gift of the spirit is associated with the sprinkling with water. In Matthew 3:16, there is an account of two baptisms. One with water, one with the Spirit. The water baptism was symbolic of the Spirit baptism. In John 7:37-38, Jesus stood and cried, saying, “If any man thirst, let him come unto me and drink. He that be- lieveth on me, as the scripture hath said, from within him shall flow rivers of living water. But this spake he of the Spirit, which they that believe on him were to receive.”

The third symbol is fire. In Acts 2:3-4, we * have an account of the gift of the Holy Spirit to the first group of believers. “There appeared unto them tongues parting asunder like as of fire, and it sat upon each one of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit.”

These symbols point to the Spirit and his work, and not to Christ and his redemptive action.

Now by what mode were these symbols applied? The oil was poured upon the head. The water, throughout the Jewish dispensation, was sprinkled or poured, and the fire descended upon the heads of the believers.

There is one other passage to which I must t direct your attention: 1 John 5:8, “There are three who bear witness, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and the three agree in one.” These three, the Spirit, the water, and the blood agree, says the Apostle. In what respect? In meaning for one thing, they all signify cleansing. Do they not agree also in mode? The blood was always sprinkled. The water of purification among the Jews was always sprinkled. And the Spirit, as we shall see, always descended upon.

It thus appears from Scripture that water baptism symbolizes the work of the Spirit. If so, it should not be supposed that the mode of baptism is by immersion.

But some — many — say that the question of mode is settled by the word baptizo, the Greek word which gives the name to the rite. We do not think so. The Greek word for the Lord’s Supper, the second Sacrament, does not settle the question of the mode of its administration. The Greek word for the Supper is deipnon, which signifies a full meal; a table spread with sufficient food to satisfy a man’s hunger. The Greek Christians at Corinth, perhaps reasoning from the meaning of that word, misobserved the Lord’s Supper; and the Apostle had to correct them. 1 Corinthians 11:20-22. If reasoning from the literal meaning of the classic word for the second Sacrament leads to error, may not reasoning from the literal meaning of the word for the first Sacrament also lead to error? It not only may, but does.

In the Lord’s Supper we have not a physical feast, as the word for it suggests, but physical signs of a spiritual feast. In baptism we have not a physical bath, but a physical sign of a spiritual cleansing. A small quantity of bread and wine is sufficient to signify a spiritual banquet. And a little water is sufficient as a sign of spiritual purifying.

But it is contended by many that baptizo always means to dip, to plunge, etc. Not in the Bible.

At the beginning of my ministry in Tennessee I attended a debate on the subject of the mode of baptism between a Baptist minister and a minister of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. The Baptist brought many books of authority by which he intended to prove that baptizo always means to dip, to plunge, etc. The Cumberland Presbyterian brought only his Bible. He said he proposed to show that baptizo in the Bible does not mean to immerse. What he proposed to do, he did.

Some years ago a Baptist publishing house in the north requested Dr. Edmund B. Fairfield to prepare a book in defense of the Baptist view of the mode of baptism. This man had been a Baptist minister for more than a quarter of a century, and no man was more certain of being right than he was. He said he had no doubt on the subject. For two years he investigated the evidence relating to the mode of baptism. To his surprise, the farther he went in his investigation, the more he saw that the evidence was against the Baptist position. In the presence of his accumulated evidence, honesty required him to surrender his former view. He wrote a book, but it was on the other side of the question.

I will now give you instances of the use of the word in the New Testament where baptizo does not, cannot, mean to immerse. Luke 11:37-38: There we are told that a Pharisee asked Jesus to dine with him; and Jesus went in, and sat down to meat. And when the Pharisee saw it, he marveled that he had not first bathed himself before dinner. The word there rendered bathed, is the word baptizo. Was the Pharisee surprised that Jesus did not first immerse himself before sitting down to meat? Impossible!

Hebrews: The author in the 9th chapter is describing the ordinances of divine service in the old sanctuary. “The priest offered both gifts and sacrifices that cannot as touching the conscience make the worshipper perfect, being only (with meats, drinks, and divers washings) carnal ordinances.” The word rendered washing is baptizmois. These washings were called baptisms. There were many washings, purifyings, among the Jews, but no immersions.

The third instance of the use of the word baptizo, where it cannot mean immerse, is in the accounts of the baptisms with the Holy Spirit. John the Baptizer, (would you say John the Immerser?) says: “I indeed baptize you with water; but there cometh he that is mightier than I; . . .He shall baptize you with the Holy Spirit.” Was baptism with the Holy Spirit by immersion? Was anybody ever immersed in the Holy Spirit? The idea is foreign to Scripture, foreign to reason. The Spirit was always applied to the person, never the person to the Spirit. The same is true of water in the Bible. It is always applied to the person, and that by sprinkling. The immersionist applies the person to the water, we apply the water to the person, that is the Bible way, there is no exception.

The same is true of the use of blood in the Bible, as we have seen. There is a song we sometimes sing:

“There is a fountain filled with blood,

Drawn from Immanuel’s veins;

And sinners plunged beneath that flood,

Lose all their guilty stains.”

I like the music, but not words of the first stanza. The words are thoroughly unscriptural. When was any sinner ever plunged beneath a flood of the blood!

Let Peter tell you how the blood was applied. His First Epistle addressed to the “elect . . . according to the foreknowledge of God the Father, in sanctification of the Spirit unto obedience and the sprinkling of the blood of Jesus Christ.” And listen to the author of Hebrews: “Having a great priest over the house of God, let us draw near with a true heart in fullness of faith, having our hearts sprinkled from an evil conscience, and our bodies washed with pure water …” 10:21-22. The washing with pure water is a reference to water baptism. In the passage there are two cleansings, the cleansing of the body and the cleansing of the heart. It says that the heart was cleansed by sprinkling. Was the body cleansed by immersion?

Now all will agree that the greater, the better baptism, is the Spirit baptism. John says: “I baptize you with water, but he that cometh after me shall baptize you with the Holy Spirit.” John’s baptism was typical of Jesus’ baptism. Jesus’ baptism with the Spirit was the real, the important baptism. For the mode of it, read Joel’s prophecy: “It shall come to pass that I will pour out my Spirit in all flesh; and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, your old men shall dream dreams, your young men shall see visions and also upon the servants and the handmaids in those days will I pour out my Spirit.” 2.28-29. Now read the account of the fulfillment of that prophesy in Acts 2:3-4: “There came from heaven tongues parting asunder like as of fire, and it sat upon each one of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit.” The tongues of fire and the Holy Spirit came from above, from heaven, upon the believers.

In Acts, the 10th chapter, we are told that while Peter was yet speaking, the Holy Spirit fell on all them that heard the word. That is the invariable rule, the Spirit always falls upon, descends upon, or is poured upon the subjects. If water baptism is to present a picture of Spirit baptism, it should be in mode like Spirit baptism. Well, if the mode is not given in the word which designates the rite, how are we to learn what the mode is? In two ways: 1. By the meaning of the rite in Scripture. I have dealt with that already. 2. By the examples of its administration. The passages in the New Testament that relate to the administration of baptism are divided into three classes: First, those which taken by themselves seem to favor immersion. Matthew 3:16. The authorized version says that Jesus when he was baptized went up straightway out of the water. The revised version says that he went up straightway from the water. The preposition used is not ex, meaning out of, but apo, which means from the water. He could have gone up from the water without going up out of the water. In Acts 8:38-39, we have an account of the baptism of the eunuch by Philip. The record says that both went down into the water, both Philip and the eunuch; and he baptized him. And when they came up out of the water the Spirit of the Lord caught away Philip. The immersionist says that this language indicates that the baptism was by immersion, but t the passage, correctly read, indicates no such thing. If going into the water and the coming up out of it were parts of the baptism, then both Philip and the eunuch were baptized; for they both went down into the water and came up out of the water. The passage says that the Baptism took place between the going into the water and the coming up out of the water. And all the lawyers of Philadelphia cannot tell how the baptism was performed. No valid argument can be based on prepositions. In the 8th chapter of the Acts, the preposition en is used several times, but only in the account of the baptism of the eunuch is it translated into. Elsewhere in that chapter it is translated at, by, etc. So I say that this class of Scripture only seems to favor immersion.

Second, there is a second class of passages relating to the administration of baptism from which the idea of immersion is excluded. Under this head belong the accounts of baptism with the Holy Spirit. With this class of passages we have dealt already.

Third, there is a third class of passages which, in themselves, are not decisive, but which are altogether favorable to baptism by sprinkling. First, the baptism of the 3,000 at Jerusalem. Was it by immersion? Where? In what water? Jerusalem’s water supply was mostly in cisterns under the ground, no river flowed by Jerusalem, only a little brook which was a wet weather branch, at other seasons its bed was dry. There was no large pool or lake at Jerusalem. If there had been, it would have been under the control of the Pharisees, who, of course, would have forbidden it to those despised followers of the crucified pretender to Messiahship. It there had been a body of water sufficient for baptism by immersion and the Apostles had used it for that purpose, the whole body of the water would have been polluted, rendered unfit for use by any Jew fearing defilement. The facts of the situation in Jerusalem are dead against the notion that the 3,000 converts were baptized by immersion.

Take now the baptism of the case of the eunuch, which was down toward Gaza, which was desert. Some tourists were shown the place where it was said the eunuch was baptized. And what did they see? A little stream no bigger than your little finger flowing out of a rock. A Baptist in the party exclaimed, “Oh it didn’t take place here, it didn’t take place here, not enough water,” Exactly, not enough water for immersion, but a plenty for sprinkling.

Next, the case of Cornelius and his household. While Peter was yet speaking the Holy Spirit fell on all that heard the Word. Did Peter say, “Is there a baptistry here, or a pool convenient where these may be baptized?” No, he said, “Can any man forbid the water that these should not be baptized?” He then commanded them to be baptized then and there. Was it by immersion?

The case of the jailer at Philippi. His baptism took place without delay at midnight at the jail. Was it by immersion? The case of Paul is peculiarly clear and convincing. Ananias was sent to administer to Paul, then called Saul. Laying his hands on him, Ananias said, “Brother Saul, the Lord has sent me that thou mayest receive thy sight and be filled with the Holy Spirit.” And straightway there fell from his eyes as it were scales, and he received his sight. And he arose and was baptized. Baptized then and there, standing up. Was it by immersion?

Two points more and I am done.

- According to our view of baptism there is unity and harmony in Scripture. There is one method of purification in Both Testaments and that is by sprinkling — sprinkling of water, sprinkling of blood.

- Baptism by sprinkling is universally applicable. Universally applicable as to place. Wherever there is water enough to sustain life, there people can be baptized by sprinkling. In World War I there was a large military camp in Greenville, South Carolina. The Baptists complained that no provision was made for administering baptism by their mode. They seemed to think that the government should run a river into the camp, or create a lake for their convenience. A distinguished Baptist minister, Dr. Norwood, pastor of City Temple, London, England, was a Chaplain at the battle front in France. He said the application of the rite of baptism by immersion was out of the question there. He said he did not repudiate that mode of baptism, he simply had no use for it in that situation. He could never again insist that the quantity of water was important in Baptism.

Baptism by sprinkling is universally applicable as to time. It can be safely administered in the frozen North in winter, as in the balmy South.

It is universally applicable as to people. It can be applied to infants as well as to adults; to the sick as well as to the healthy; to the dying as well as to the living.

Remember, according to the Bible, people were baptized with water, not in water; they were baptized with the Holy Spirit, not in the Holy Spirit. The water was applied to the person, not the person to the water. The Spirit was applied to the person, not the person to the Spirit. And believers were baptized immediately on the spot.

Reasoning from the use of baptizo in Scripture, from the meaning of the rite of baptism, and from the instances of its administration, we conclude that baptism was, and should be now, by sprinkling or pouring.

“I will sprinkle clear water upon you,” sayeth the Lord, “and ye shall be clean; from all your filthiness, and from all your idols, will I cleanse you.” “Wherefore, let us all draw near with a true heart in fullness of faith, having our hearts sprinkled from an evil conscience and having our bodies washed with clean water.”

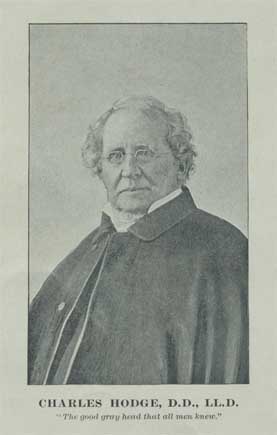

Hodge’s death came on this day, June 19, in 1878. Then early in July of that same year on the pages of The Christian Observer, this brief note appeared under the title, “Calvinism and Piety,” :

Hodge’s death came on this day, June 19, in 1878. Then early in July of that same year on the pages of The Christian Observer, this brief note appeared under the title, “Calvinism and Piety,” :

Because it is generally agreed that the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper refers to the death and resurrection of Christ. If baptism also signifies the death and resurrection of Christ, then we have two Sacraments which are signs and symbols of the same facts of the life of Christ. Why this double representation of these facts? In that case we have no sign and symbol of the work of the Holy Spirit. In the Old Testament it was not so. There the passover pointed to the work of Christ, but circumcision pointed to the work of the Holy Spirit. For circumcision meant the putting away of carnality, the removal of the sinful flesh. This is the peculiar work of the Holy Spirit. Baptism means the same thing; it means the washing away of sin. We object to the immersion- ist’s view of the meaning of baptism for another reason. The burial of Christ has no redemptive value. Christ would have saved the world if he had not been buried. Why should a rite be ordained to signify a fact which is not essential to the accomplishment of salvation?

Because it is generally agreed that the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper refers to the death and resurrection of Christ. If baptism also signifies the death and resurrection of Christ, then we have two Sacraments which are signs and symbols of the same facts of the life of Christ. Why this double representation of these facts? In that case we have no sign and symbol of the work of the Holy Spirit. In the Old Testament it was not so. There the passover pointed to the work of Christ, but circumcision pointed to the work of the Holy Spirit. For circumcision meant the putting away of carnality, the removal of the sinful flesh. This is the peculiar work of the Holy Spirit. Baptism means the same thing; it means the washing away of sin. We object to the immersion- ist’s view of the meaning of baptism for another reason. The burial of Christ has no redemptive value. Christ would have saved the world if he had not been buried. Why should a rite be ordained to signify a fact which is not essential to the accomplishment of salvation?