We are pleased to have Dr. David W. Hall with us today as guest author. Rev. Hall has served as the pastor of the Midway Presbyterian Church in Powder Springs, Georgia since 2003. Prior to that, he was pastor of Covenant Presbyterian in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. While at Covenant, he was able to host an Internet-based magazine called Premise, one of the earliest Christian magazines to appear on the Internet. It began in 1994 and had a five-year run, ending in 1999. Twenty years ago! Ancient history, when speaking of the Internet!

Premise was taken down off the Web quite some time ago, but the PCA Historical Center is grateful to have been able to preserve the magazine’s content. Dr. Hall’s article, which follows, is part of that content, and we hope to make more Premise articles available in the future.

Francis Makemie and Freedom of Speech

by Dr. David W. Hall.

One illustration of how religion and politics were interwoven, especially the religion and politics of strongly Scottish Calvinist sentiment, can be seen from the experience of Ulster Presbyterian missionary Francis Makemie (b. 1658). Makemie had been reared on tales of the Scottish rebellion that adopted the Solemn League and Covenant, and he was educated at the University of Glasgow one generation after Samuel Rutherford. Commissioned by the Presbytery of Laggan, a fiercely Calvinistic stronghold, the first Presbyterian minister on the North American continent landed on the eastern shore of Chesapeake Bay in 1683. Over time, he earned a reputation as a threat to the Anglicans in the area, and he was reported to the Bishop of London (who never had authority over Makemie) to be a pillar of the Presbyterian sect. His work was commended by Puritan giant Cotton Mather, and his correspondence with Increase Mather indicates considerable commonality of purpose among early American Calvinists. Cotton Mather would later recommend a Catechism composed by Makemie for his New England churches.

One illustration of how religion and politics were interwoven, especially the religion and politics of strongly Scottish Calvinist sentiment, can be seen from the experience of Ulster Presbyterian missionary Francis Makemie (b. 1658). Makemie had been reared on tales of the Scottish rebellion that adopted the Solemn League and Covenant, and he was educated at the University of Glasgow one generation after Samuel Rutherford. Commissioned by the Presbytery of Laggan, a fiercely Calvinistic stronghold, the first Presbyterian minister on the North American continent landed on the eastern shore of Chesapeake Bay in 1683. Over time, he earned a reputation as a threat to the Anglicans in the area, and he was reported to the Bishop of London (who never had authority over Makemie) to be a pillar of the Presbyterian sect. His work was commended by Puritan giant Cotton Mather, and his correspondence with Increase Mather indicates considerable commonality of purpose among early American Calvinists. Cotton Mather would later recommend a Catechism composed by Makemie for his New England churches.

Makemie organized at least seven Presbyterian churches committed to the Westminster Confession of Faith and Scottish ecclesiastical order between 1683-1705. In between the organizing of churches along Scottish models—the Scottish League and Covenant seemed to be blossoming in America, perhaps more than in its native Scotland—Makemie served as a pastor in Barbados from 1696 to 1698. He also sheltered persecuted Irish Calvinist ministers from 1683-1688. Following the Glorious Revolution in 1688 the need for shelter in America diminished, and some of these religious refugees returned to Ireland and Scotland. Makemie, however, remained in America, found a wife, and continued organizing Presbyterian congregations throughout Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. In a 1699 letter, Makemie still spoke reverentially of Geneva as a Calvinist center.

Ministers from the Church of England protested Makemie’s church planting, caricaturing his ministry as subversive and nonconformist. Eventually the Sheriff of Long Island at the behest of the British Governor of New York, Lord Cornbury arrested Makemie and another Presbyterian colleague, John Hampton, for preaching without a license by. On January 21, 1707, the warrant for their arrest charged them with spreading “their Pernicious Doctrine and Principles” in Long Island without “having obtained My License for so doing, which is directly contrary to the known laws of England.”

Cornbury’s oppressiveness was well known from several earlier cases, and Makemie realized that if freedom of religion were not granted in one colony, America would never have the kind of free expression needed. He may have viewed New York as a mission for religious freedom; en route to Boston from New Jersey, he could have simply avoided Cornbury’s territory. In what would become one of the earliest tests of freedom of speech in America, this Irish Calvinist was indicted by an Anglican authority (also exposing an early establishment of religion in New York) and held for two days prior to trial.

Makemie appeared before Cornbury (who called the missionary “a Disturber of Governments”) in the council chamber at Fort Anne, New York, on the afternoon of January 23, 1707. Lord Cornbury (Edward Hyde) charged: “How dare you take upon you to preach in my Government without my License”! Makemie answered that Parliament had granted liberty to preach in 1688 under William and Mary. Cornbury contended that such laws did not extend to the American colonies. Makemie answered that the act of Parliament was not restricted to Great Britain alone, but applied to all her territories; Makemie also produced certificates from courts in Virginia and Maryland that had already recognized his work. When Cornbury argued that ‘all politics is local,’ including rights and penalties, Makemie reminded him and his attorneys that the Act of Toleration was applicable in Scotland, Wales, Barbados, Virginia, and Maryland, and that without express restriction it was also applicable in all “her Majesties Dominions”—unless, of course, New York was not considered under her dominion.

Notwithstanding, Cornbury did not want Makemie or other “Strolling” preachers in his territory. Makemie further argued that strolling Quakers were permitted religious liberty in the colonies, which brought Cornbury’s equal-opportunity-oppressor rejoinder: “I have troubled some of them, and will trouble them more.” When Cornbury revived his charge that Makemie was spreading “pernicious doctrines,” the Ulster missionary answered that the Westminster Confession of Faith was very similar to the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England and challenged “all the Clergy of York to show us any false or pernicious doctrines therein.” Makemie even stated his willingness to subscribe to the Thirty-Nine Articles should that satisfy the Governor.

Earlier Makemie had applied to the Governor to preach in a Dutch Reformed Church in New York and had been denied permission. His speaking in a private home gave rise to the charge of preaching unlawfully. Cornbury reiterated that Makemie was preaching without license, charging him to post bond for his good behavior and to promise not to preach again without licence. Although he disputed any charges against his behavior, Makemie consented to post bond for his good behavior (knowing there were no provable charges), but he refused to post bond to keep silence, promising in Lutheresque words that “if invited and desired by any people, we neither can, nor dare” refuse to preach. Like Luther, Makemie could do no other.

Cornbury then ruled, “Then you must go to Gaol?” Makemie’s answer is instructive.

[I]t will be unaccountable to England, to hear, that Jews, who openly blaspheme the Name of the Lord Jesus Christ, and disown the whole Christian religion; Quakers who disown the Fundamental Doctrines of the Church of England and both Sacraments; Lutherans, and all others, are tolerated in Your Lordships Government; and only we, who have complied, and who are still ready to comply with the Act of Toleration, and are nearest to, and likest the Church of England of any Dissenters, should be hindered, and that only the Government of New-York and the Jersies. This will appear strange indeed.

Cornbury responded that Makemie would have to blame the Queen, to which the defendant answered that he did not blame her Majesty, for she did not limit his speech or free religious expression. At last, Lord Cornbury relented and signed a release for the prisoners, charging both Makemie and John Hampton, however, with court costs. Before leaving, Makemie requested that the Governor’s attorneys produce the law that delimited the Act of Toleration from application in any particular American colony. The attorney for Cornbury produced a copy, and when Makemie offered to pay the attorney for a copy of the specific paragraph that limited the Act of Parliament, the attorney declined and the proceedings came to a close.

In a parting shot, Lord Cornbury confessed to Makemie, “You Sir, Know Law.” Makemie was later acquitted, and free speech and free expression of religion, apart from government’s approval, took a stride forward in the New World. Makemie pioneered religious liberty at great risk, and all who enjoy religious freedom remain in debt to this Scots-Irish son of Calvin.

In a parting shot, Lord Cornbury confessed to Makemie, “You Sir, Know Law.” Makemie was later acquitted, and free speech and free expression of religion, apart from government’s approval, took a stride forward in the New World. Makemie pioneered religious liberty at great risk, and all who enjoy religious freedom remain in debt to this Scots-Irish son of Calvin.

Upon hearing of Makemie’s eventual (though delayed) release, the esteemed Cotton Mather wrote to his colleague the Rev. Samuel Penhallow on July 8, 1707: “That Brave man, Mr. Makemie, has after a famous trial at N. York, bravely triumphed over the Act of Uniformity, and the other poenal laws for the Church of England, without permitting the matter to come so far as to pleading the act of toleration. He has compelled an acknowledgement that lawes aforesaid, are but local ones and have nothing to do with the Plantations. The Non-Conformist Religion and interest is . . . likely to prevail mightily in the Southern Colonies. I send you two or three of Mr. Makemie’s books to be dispersed. . . .”

In another blow for religious freedom, the next year a Somerset County, Maryland, court approved the certification for a Protestant Dissenter church to be established. By a narrow 3-2 vote of the court, Makemie secured liberty for Presbyterian churches under “an act of parliament made the first year of King William and Queen Mary establishing the liberty of Protestant Dissenters.”

Makemie was also instrumental in laying the groundwork for an Irish priest, William Tennent, to immigrate to America. Tennent would later establish the “Log College,” and one of its students, the Rev. Samuel Finley, started the West Nottingham Academy in 1741. These schools, much like Calvin’s Academy in Geneva, became the proving grounds of the American republic. From this one Academy came founders of four colleges, two U. S. representatives, one senator, two members of the Continental Congress, and two signatories of the Declaration of Independence (Benjamin Rush and Richard Stockton). Samuel Finley went on to become president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) in 1761.

This developing American Calvinism, far from the modern caricature as a narrow or severe sect, was a boost to personal freedom and civil discourse in its heyday. The first American Presbyterian pastor helped entrench the right to free expression and free worship by appealing to the principles of the Glorious Revolution. A tidal wave of Calvinistic thinking came to America through immigrants like Makemie and continued to radiate outward.

Images :

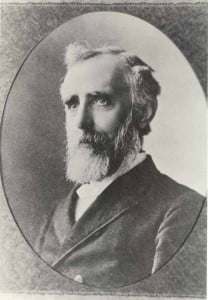

1. The trial of Francis Makemie

2. Commemorative statue of Francis Makemie